My father lived 7 years past his retirement, and then a sudden heart attack took him away. Those 7 years were filled with hunger for learning, thirst for knowledge, zest for understanding. He read constantly; kept a cheap spiral notebook and a dictionary beside his overstuffed chair.

In the notebook, Dad copied unfamiliar words in a precise hand, then wrote the definitions, complete with diacritical markings for pronunciation.

One autumn day I knew he was near the end; could see it in his eyes, his face; hear it in his voice that quavered where quaver had never been.

The end was sudden; a shock to Mom and us kids, all adults. No lingering illness, no hospitalization, no indignity. Just lights-out, and gone.

An enormous blessing— thank You, Lord — for the end of a life well-lived.

Nothing to lose

Dad was born in 1914. He turned 20 in the depths of the Great Depression, 1934, in a medium-size town in rural Kansas. There were virtually no resources in the family, no cash. “I had a pair of shoes for every occasion,” he would say with self-abasing dry humor. “I wore them to school, to work, to the dance on Saturday night, and to church on Sunday morning.”

At wartime, he enlisted 10 months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. He spent 6 years in the U.S. Navy, then returned home. From his father-in-law, he bought a small farm to raise boys with his wife, and slowly began to claw his way up out of poverty. A Post Office job was a godsend, and finally there was cashflow. Not much, but some.

Learning as entertainment

At 65 he retired, his government years having bridged to his Navy service, and for once in his life he had time to chase intellectual pursuits.

He enrolled in an evening welding class for adults at the high school, offered during the summer break.

I gave him a copy of James Michener’s Centennial, knowing he would like the cowboy stories and the tale of western migration. He devoured the paperback, then glued himself to the TV for the 1979 mini-series. Talked about it for months afterward.

He started reading a hard-back copy of The Living Bible, new in the 1970s, marking passages here and there with a yellow highlighter.

He got out Mom’s electric sewing machine, visited a fabric shop in town, and began to sew.

What??? Sewing???

He needed a shop apron for automotive maintenance; a small, rugged bag for a travel kit of hand tools; a long, narrow zippered sleeve to organize a socket set.

The zipper on the socket sleeve was bordered with bright fabric. After his funeral, I found a handwritten note wrapped around the 3/8-inch-drive sockets within. In his meticulous cursive, he had written: “The zipper is ‘peach,’ if you want to know.”

Michener and maps

On the day before he died, I visited home, spent the night in my old room on the farm. When I had arrived in the late afternoon, he was ready for me. “Step into my office, Mister,” he said as I climbed out of my Mini Cooper. “Got somethin’ to show ya.”

Step into my office could mean anything from his workshop to the barn to the garage to the bathroom. In this case, it was the kitchen.

I followed him into the house where he had cleared the dining table for a large map.

“You heard of the Moffat Tunnel?” he asked.

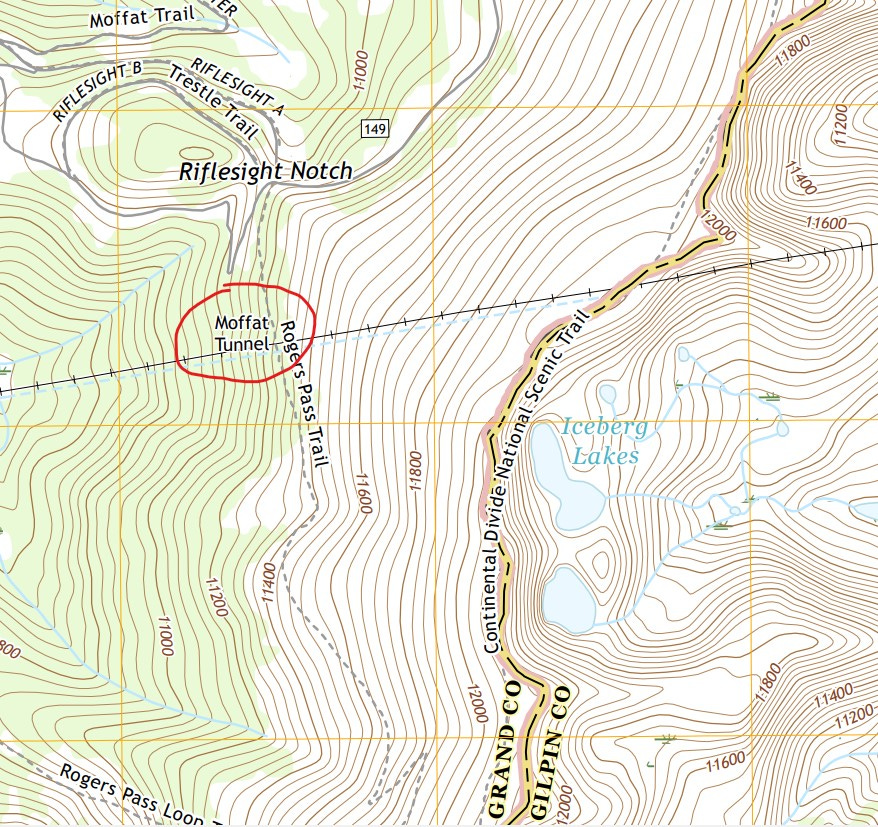

I stared at the map. It was like none I had seen before, plastic-like waterproof paper, all green and brown lines with printed place names. Blue squiggles that must have been rivers or tributaries. Across the top it said US Geological Survey, Topological Map. It showed an area near Denver, Colorado.

“Well,” I hesitated. “Maybe. Doesn’t it have something to do with a railroad?”

He nodded approvingly. “Potato Brumbaugh needed to get water to his potatoes,” he said, referring to a fictitious character in Centennial. “After he had a stroke he couldn’t speak, but he sat on his porch looking at the potato field and thinking about how to get water to the crop. You remember the story?”

“Sort of,” I hedged. The Potato Brumbaugh-as-elder episode was toward the end of the book, and when I had read it with 20-something impatience, the exciting cowboy stories were in earlier pages. I had no real interest in irrigating the potato field, stroke or no.

“He envisioned a tunnel from the high Rockies down to the flatlands on the east,” Dad continued, real interest in his voice. He gestured to the map. “You see the peaks here,” he took the ever-present mechanical pencil from his shirt pocket and used it as a pointer, “and Brumbaugh figured a tunnel or a canal somewhere around here” — he swept the pencil from northwest to southeast — “would provide irrigation.”

He straightened up from his bent-over position, and I noted the physical effort. He was no longer the smooth and limber man I had known. His breath came in shallow puffs.

“So, did he build one?” I asked, trying to muster interest in the subject that had clearly fascinated Dad.

“No, of course not.” He glanced at me with a slight frown. “He had had a stroke, right?”

“Right, sure.” I felt foolish. Try to stay engaged, I chastised myself. Act interested. I glanced at him from the corner of my eye, and unbidden, the word frail came to my mind. I brushed the thought aside.

“And he died before he could tell anybody,” Dad was saying, concentrating on the map. “But he had a brainstorm all the same: If he could build the tunnel, he could irrigate cropland in the high desert of eastern Colorado.” He paused, still staring at the map. “But of course he could not tell anybody his idea.”

He found it!

“So…” I began, trying to tie the story together with the map, “there is no tunnel.”

“But there is!” he announced proudly, pointing again, and handing me a small magnifying glass. Through the lens, I made out tiny black letters spelling Moffat Tunnel.

“I remembered reading about it in the newspaper before the war,” he said. “A guy named Moffat had an idea that they could run a train through the Continental Divide by drilling a railroad tunnel under the mountains. It was just like Potato Brumbaugh’s idea of moving water down. But in this case, it was the train that moved.”

I gazed at the map and wondered at his wonder. In the newspaper before the war. This was 40 years ago.

Anyone who stops learning is old, whether at twenty or eighty. Anyone who keeps learning stays young. — Henry Ford

“Where did you get the map?” I asked.

“From someplace in D.C.,” he said. “I went to the Library in town. They didn’t have a copy there, but I found a book from the USGS on the shelf. There was a page in the back that gave an address to write to. I sent them a check for $10, and in due time the map showed up.”

Interest breeds enthusiasm

I marvel at it even today, thinking of the 72-year-old man laboriously climbing the steps to the public library, talking to the librarian, shuffling through the stacks, laying out dusty volumes on a reading table. Probably asking for a magnifying glass to study the fine print.

Who does such things?

People who are curious, that’s who. People who love life.

Dad was an adherent of lifelong learning decades before any professional educator ever thought that was a thing.

Do you have a Curious List?

The Curious List is a matter of following intellectual pursuits, one of the areas key to a fulfilling retirement. In my dad’s case, it would have included: Welding, Bible, sewing and geology.

Or maybe trains, or maybe the Rocky Mountains. Whatever.

The point was, he went to some lengths to be involved in each. It kept him vital, engaged, interested and motivated. Until literally his last day.

What does the Scripture say?

The heart of the discerning acquires knowledge, for the ears of the wise seek it out.

Proverbs 18:15 (NIV)

Challenge Question

What’s on your Curious List?

Download the Challenge Tracker to see a list of “starter suggestions,” topics that will spur your interests. Identifying a subject of curiosity does not mean you have to go all-in; it just means you would like to learn more about it. Hunting, gardening, rain forests, Grand Canyon, sky diving, spelunking, South African diamonds, whaling ships.

Important note: As an example, you do NOT have to jump out of an airplane to learn about sky diving: Where did it come from? Who thought of it? Who was the first to test it? What was the military’s role? What are the commercial applications for it? How much does it cost? Is there a local club? What sorts of people do this?

Find an interest, write it down, make plans to learn more, and chase it down.

Download the Challenge Tracker. It’s free.

When you take up such an interest, people will look at you like you’re crazy. Maybe they’ll be right. Or maybe they simply haven’t invested enough energy in their own Curious List.

Chase your interests. See where they lead. It’s that time of life.

Share this post